Many are curious about the mysterious imperial feast. How did the emperor dine? Let us explore the fascinating imperial meals today!

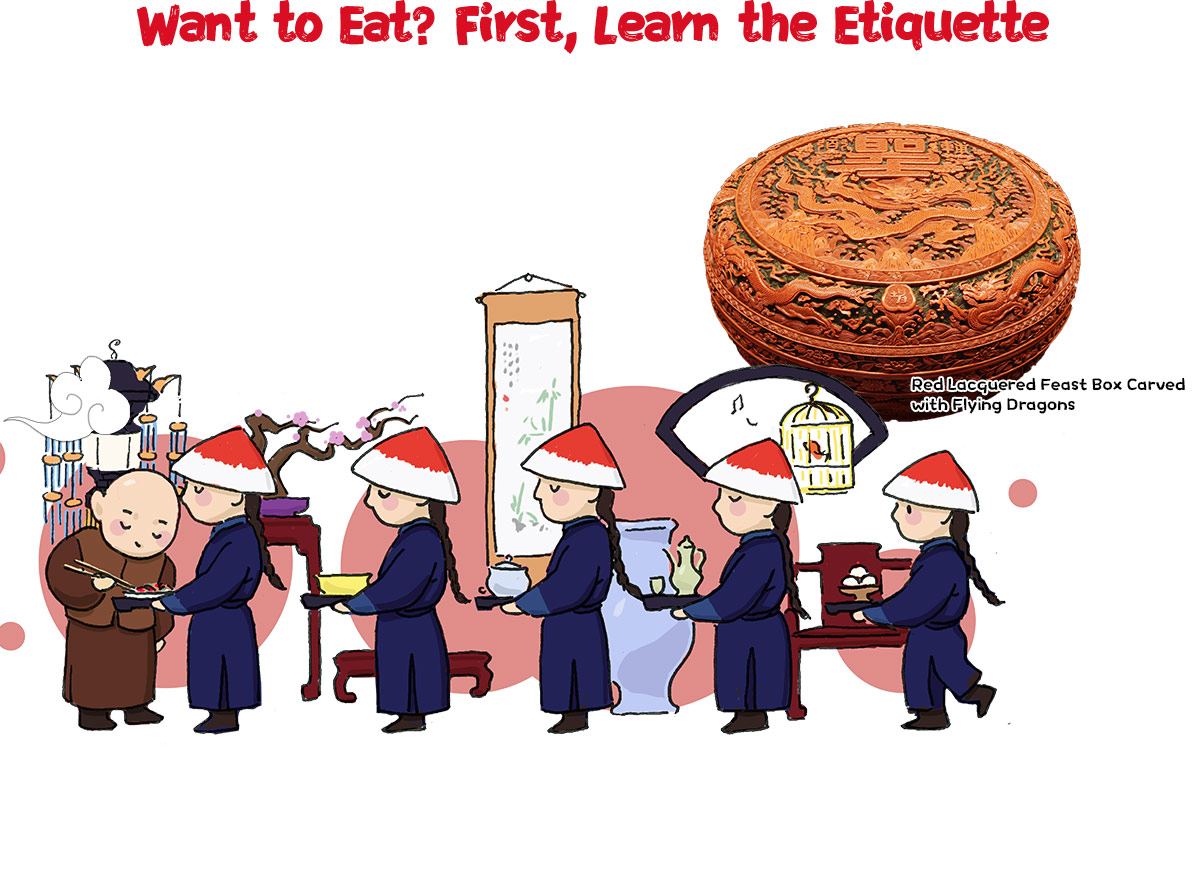

China, the land of etiquette, held especially rigorous standards for the imperial family. If you feel hungry today, you simply wash your hands and wait at the table. But for the imperial family, dining was an elaborate process governed by strict rituals. From the emperor to his consorts and concubines, every meal followed a ceremonial procedure known as "bestowing food" or "offering up food." Before dining, the emperor would first offer up dishes to the empress dowager. Similarly, the empress, consorts, concubines, and princes (including the emperor’s children) would offer up dishes to the emperor, symbolising respect for elders and loyalty to the sovereign. The empress dowager, in turn, would bestow food upon the emperor to show care for the younger generation. After the emperor finished dining, he would reward leftover dishes, pastries, and desserts to his consorts and children. However, much of this process was handled by palace maids, so their masters simply needed to be aware and approve.

Now that respectful and caring feelings have been received, it’s time to satisfy the hunger and chomp down, right? Not so fast! The dining was only beginning! One interesting role in the Imperial Kitchen (Yushan fang) was the eunuch “carrying the table”. Before the emperor dined, three square tables were arranged and covered with gold-embroidered cloth. Then, other eunuchs would bring in red lacquered boxes, lining up to have meals arranged on the table. These meals included various dishes, steamed buns, twisted rolls, pastries, rice, cakes, and soups. Since ancient times, silver was believed to be able to detect poison, so once the emperor was seated, a special eunuch would use a silver plate to test each dish. Only when no colour change occurred could the emperor eat safely.

In TV dramas, we often see the emperor dining with his consorts, but in reality, he usually ate alone. According to palace rules, no one was allowed to share a table with the emperor unless given special permission. The empress dowager, empress, consorts, and concubines also dined in their respective palaces.

You might be surprised that the emperor, occupied with myriad state affairs, had no fixed dining location. Sometimes, he ate in his bedchamber and sometimes in his office. While the locations varied, the allotted portions did not. Here, the allotted portion means that the Imperial Kitchen would allocate food, including rice, flour, meat, eggs, and more, to their masters according to their different statuses. The emperor's allotted portion was naturally the largest, with everyone else's decreasing by rank. As the saying goes, “A grand chancellor’s belly is big enough to hold a boat”—so what could an emperor's belly contain? Let's take a look at his daily meals!

Upon seeing this, are you shocked? How could the emperor possibly eat all this food by himself! Isn't that too wasteful? Don't worry—people in ancient times also practised the "Empty Plate Campaign". Even the emperor couldn't fill his belly with all of them, so many dishes were just displayed for show. According to the rules, these dishes could be given to others after the meal. The leftovers from the emperor and empress were generally distributed to consorts, princes, princesses, and ministers, while the leftovers from the consorts often went to the palace maids and eunuchs. In short, while the seemingly extravagant menu might appear excessive, it certainly wouldn't go to waste.

After reading about the emperor’s grand menu, you might worry about his health. Wouldn’t he eventually "grow as round as a ball"? Surprisingly, there were no overweight emperors in their portraits of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Was the Aisin Gioro family blessed with a “can’t gain weight” gene? Not quite. The emperor’s workload was heavy; in the palace, only two meals were served daily—breakfast and dinner. Breakfast took place between 7 and 9 AM, and dinner was held between 1 and 3 PM, which was very different from our dinner time today. However, you need not worry about the emperor starving and losing sleep because, between meals, he could enjoy snacks, including various pastries, wontons, and other delicacies. So, if you see in palace dramas that the emperor seems to want a feast every night, it's likely just a fabrication.

Chinese people love lively gatherings, and whether during festivals or joyous occasions in the family, friends and relatives are always invited to celebrate together. Emperors, too, enjoyed hosting various banquets. The Qing dynasty court had a wide range of banquets, each with its distinct etiquette. Such an important and complex affair naturally required a dedicated department to manage it. Thus, in the first year of Emperor Shunzhi's reign, the Qing dynasty established the Court of Imperial Entertainments (Guanglu si), an institution responsible for overseeing state banquets! Apart from the inner court banquets and clan banquets like the kinsfolk gatherings managed by the Imperial Household Department (Neiwu fu), the other main court banquets of the Qing dynasty were all organised by the Court of Imperial Entertainments, which functioned like the imperial banquet catering team.

The banquets organised by the Court of Imperial Entertainments were ranked by tiers, such as first-tier and second-tier banquets. You might assume that a first-tier banquet would surely be for the emperor, but you’d be mistaken! In the Qing dynasty, the dead were held in the highest respect, so the top three tiers of banquets were actually reserved for the deceased. The living, including the emperor, typically dined from the fourth-tier banquet. For example, New Year’s feasts, birthday celebrations for the emperor or empress dowager, Winter Solstice banquets, the emperor’s wedding, the army’s triumphant return, and the marriages of princesses and commandery princesses all followed the fourth-tier standard. So, how was the emperor’s banquet? According to historical records, a fourth-tier banquet cost approximately 4.43 taels of silver—equivalent to several months’ income for an average household at the time! And the fifth and sixth-tier banquets were typically for foreign envoys.

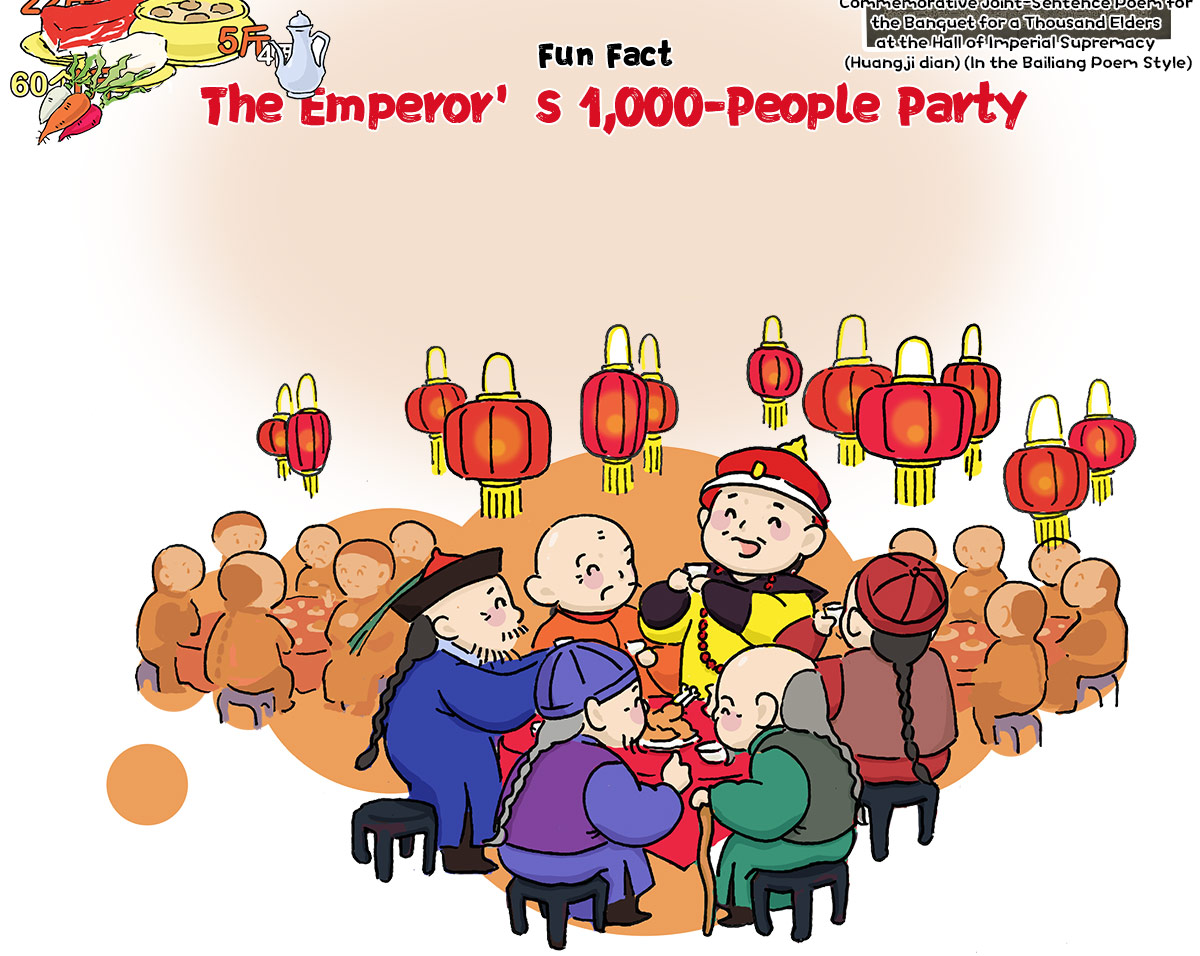

Throughout the Qing dynasty, the grandest banquets were the Banquets for a Thousand Elders (Qiansou yan). These banquets were first initiated by Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661-1722) on his 60th birthday, when he invited elderly people from across the empire to celebrate with him at the Garden of Eternal Spring (Changchun yuan) in the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan). Emperor Qianlong (r. 1736-1795), even more enthusiastic about hosting banquets, delighted in holding various gatherings, including banquets for courtiers, clan member banquets, tea banquets, great Mongolian yurt banquets, and foreign envoy banquets. He hosted the Banquets for a Thousand Elders twice, each time with thousands of attendees. The one held for his 85th birthday was unprecedented, with over 5,900 elders in attendance. Beyond simply bringing joy to the retired Emperor Qianlong, this banquet aimed to promote the value of respecting and caring for the elderly among the people. Every elderly guest enjoyed a lavish Manchu-Han Imperial Feast in the palace, received toasts from princes, ministers, and even the emperor himself, and was granted a silver longevity plaque by imperial decree. Thousands of elders received such honour at the two banquets for Emperor Qianlong’s 74th and 85th birthday.