You’ve likely heard of the saying “On the second day of the second lunar month, the dragon raises its head,” but have you ever heard of another saying – “On the third day of the third lunar month, the Yellow Emperor was born”? In ancient China, the third day of the third lunar month was celebrated as the birthday of the Yellow Emperor, known as the Shangsi Festival, a holiday dedicated to honouring him. On this day, people would gather by the water to feast and take springtime excursions. It was on this special day that Lantingji Xu, revered as the “No.1 running script handwriting in the world”, was born. So what is this story?

During the Wei and Jin dynasties period (220–420 CE), literati would celebrate the Shangsi Festival with feasts by the water, where they invented a popular game known as “floating wine cups on a winding stream” (Qushui liushang). Qushui refers to a winding stream, and shang meant a wine cup in ancient times. How was the game played? A wine cup, filled to the brim, would be set adrift in the stream. When the cup spun around or stopped in front of someone, the person had to compose a poem on the spot; failure meant a drinking forfeit.

On the third day of the third month in the ninth year of the Yonghe Era (353 CE), the renowned calligrapher Wang Xizhi gathered with 42 illustrious friends, including Xie An and Sun Chuo, at the Orchid Pavilion to play Qushui liushang. Some, inspired, created poetry with ease; others admitted defeat for bet, downing the wine. In the end, Wang Xizhi wrote a preface to commemorate 37 poems of the gathering, creating what we now know as Lantingji Xu. In a moment of creative exuberance, he wrote all 324 characters in one flowing burst on silkworm cocoon paper, each character imbued with strength and elegance. Since it was an impromptu piece, some minor revisions were needed, and he made a few adjustments directly on the paper.

The next day, after sobering up, Wang Xizhi wanted to rewrite the preface. But try as he might, he couldn’t recreate the subtle brilliance of the first version. Somewhat disbelieving, he attempted it several more times, but the initial feeling remained elusive. Thus, this masterpiece, created during a light-hearted game, became the pinnacle of running script calligraphy and has been celebrated ever since as the “No.1 running script handwriting in the world”.“天下第一行书”。

If you are familiar with calligraphy, you’ll know that the surviving copies of Lantingji Xu are all replicas. Where is the original? It’s said that Wang Xizhi regarded the work as a family treasure, passing it down through generations until it reached his seventh-generation descendant, Zhiyong. However, Zhiyong eventually became a monk, and, having no heirs, entrusted the original to his disciple, the monk Biancai.

During the early Tang dynasty (618–907), Emperor Taizong (r. 626–649) eagerly sought Wang Xizhi’s works. It is said that he had requested Lantingji Xu from Biancai three times, but was refused each time. Finally, Xiao Yi, a resourceful minister, disguised himself as a poor scholar and stayed at Yongxin Temple, gradually forming a close friendship with Biancai. Gaining his trust, he cajoled the location of the original out of Biancai, seizing it to present to Emperor Taizong. Overjoyed, the emperor treasured the work, commissioning skilled calligraphers to copy it and retaining the finest copies in the imperial collection, while keeping the original for himself.

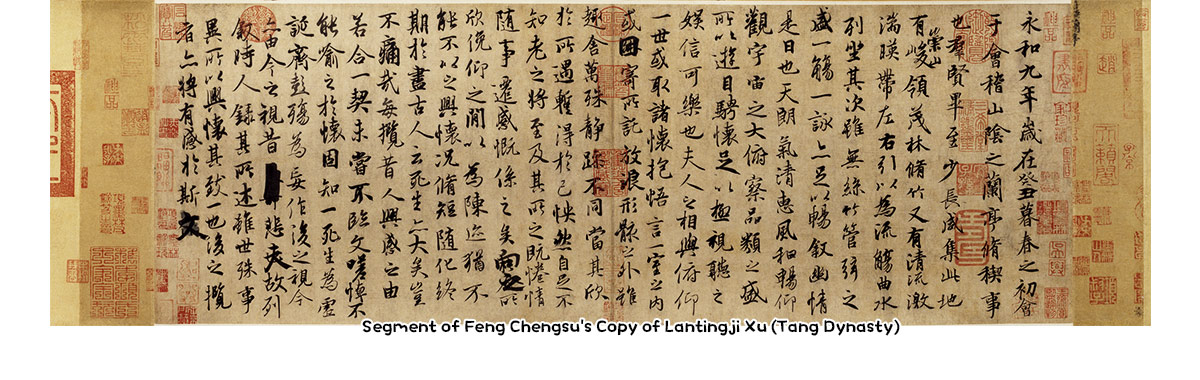

Having gone to such lengths to obtain this treasure, Emperor Taizong decreed that it accompany him into the afterlife. And so, when he passed, Lantingji Xu was buried with him, and the original has not been seen since. For centuries, people have regarded the copy made by the Tang calligrapher Feng Chengsu as the best replica, calling it "the foremost copy below the original".

Did you think only Emperor Taizong admired Wang Xizhi? Certainly not. Throughout history, many emperors cherished Wang’s calligraphy. Emperor Qianlong (r. 1736-1795) of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) had a particular fondness for Wang Xizhi’s work, frequently copying and inscribing his comments on those pieces, such as Kuaixue Shiqing Tie (Timely Clearing After Snowfall Manuscript), which he copied 73 times over 49 years.

Imagining Wang Xizhi and his friends drinking wine and composing poems amid “towering mountains, lush bamboo groves, and rushing clear streams”, Emperor Qianlong felt deep admiration. He ordered the construction of the Lantingji Xu Admiration Pavilion (Xishang ting) in the garden of the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (Ningshou gong) in the Forbidden City. Within the pavilion, he had a 27-metre winding channel carved in stone to symbolise the winding stream, calling it the “Flowing Wine Cup Channel”. Emperor Qianlong would gather with his ministers there to recreate the joy of composing poetry by the flowing water.

Moreover, Emperor Qianlong amassed eight versions of Lantingji Xu, including those by Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, Feng Chengsu, Liu Gongquan, and Dong Qichang. He had these eight versions engraved on eight stone pillars, known as the “Eight Pillars of the Orchid Pavilion” (Lanting bazhu). Initially displayed at the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) in western Beijing, these pillars now stand in Beijing’s Zhongshan Park, protected by a pavilion. If you visit, you may notice one version signed “Emperor Gaozong Hongli”—yes, Emperor Qianlong himself, a testament to his enduring admiration for Lantingji Xu.