Just as we celebrate the Spring Festival with reunion feasts, ancestor worship, and New Year greetings, the imperial palace held its own version of these cherished traditions. As early as the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), the imperial court already hosted grand ceremonies for Chinese New Year’s Day. In ancient times, the Spring Festival was also called “Yuandan”, the first day of the first lunar month. The current “Yuandan”, marking the New Year of the Gregorian calendar, was designated in 1949.

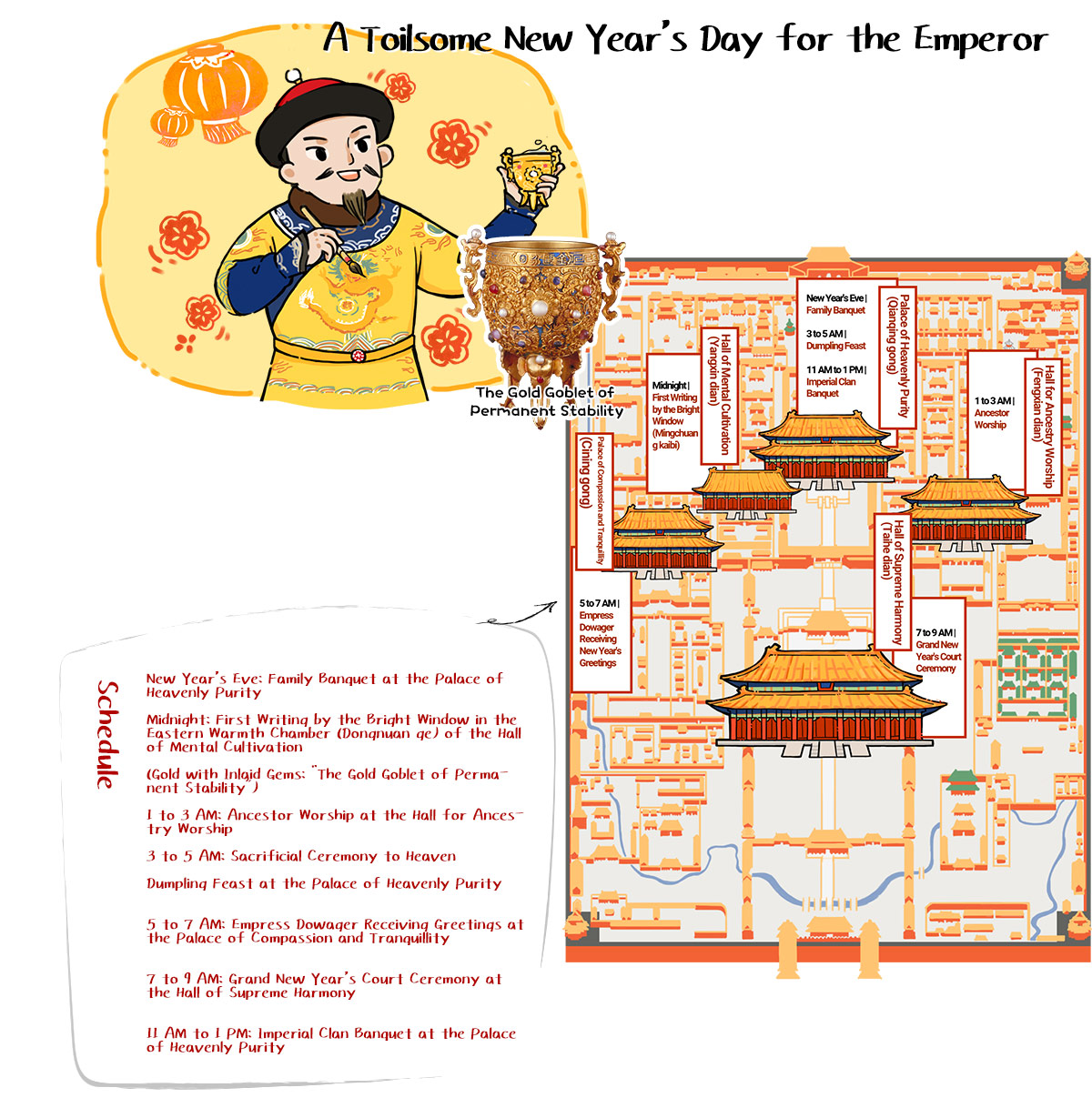

For Qing dynasty (1644–1911) emperors, New Year’s Day was far from today’s leisurely celebrations. Although there was no court-holding or memorial-reading, the emperor’s day was filled with ceremonies. As the clock struck midnight, the emperor would perform a blessing ritual in the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian), writing auspicious words like “Peace Under Heaven” and “Longevity and Eternal Spring” and pouring Tusu wine into the Gold Goblet of Permanent Stability to pray for national prosperity and an enduring empire.

Next, the emperor would proceed to the Manchu ancestral temple for the heaven-worship ceremony and to the Palace of Earthly Tranquillity (Kuning gong) with the empress to perform a ritual of worshipping deities. He would then lead nobles and ministers to the Palace of Compassion and Tranquillity (Cining gong) to pay respects to the empress dowager. At dawn, the emperor would preside over the New Year celebration ceremony in the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian), receiving blessings from civil and military officials, followed by a banquet in the same hall. Finally, after the grand ceremony, he would return to the inner court to receive greetings from his family members.

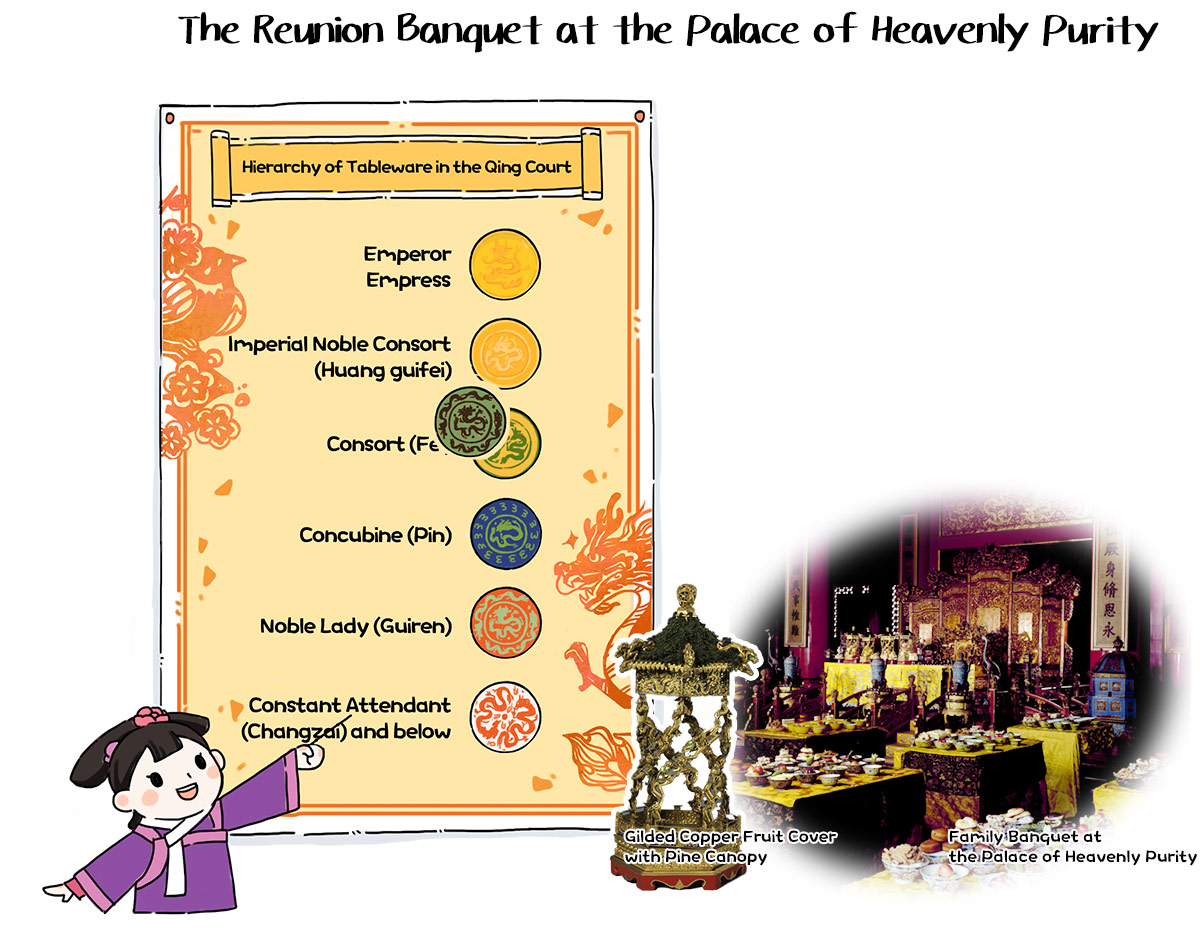

Amid all the formalities, the emperor also celebrated with his family in a reunion banquet at the Palace of Heavenly Purity. Unlike commoners, the emperor did not dine regularly with his consorts, so this feast held a unique meaning of reunion.

The banquet began at dusk (6 PM) on New Year’s Eve when the emperor took his seat. The palace was decorated with festive lanterns and auspicious couplets, and the court orchestra played harmonious tunes, filling the space with the joyous atmosphere of the New Year. While enjoying a theatrical performance for the festival, the emperor and his consorts savoured sumptuous delicacies and wine. According to Qing dynasty records, the emperor’s grand banquet table alone held 109 dishes, with an additional selection of soups and wines totalling 153 varieties.

This banquet followed strict etiquette: the emperor sat at a grand golden dragon banquet table; to his left was the banquet table for the empress facing west; both the emperor and empress used golden dragon plates and bowls; his consorts were arranged on either side, each seated according to rank and using designated tableware.

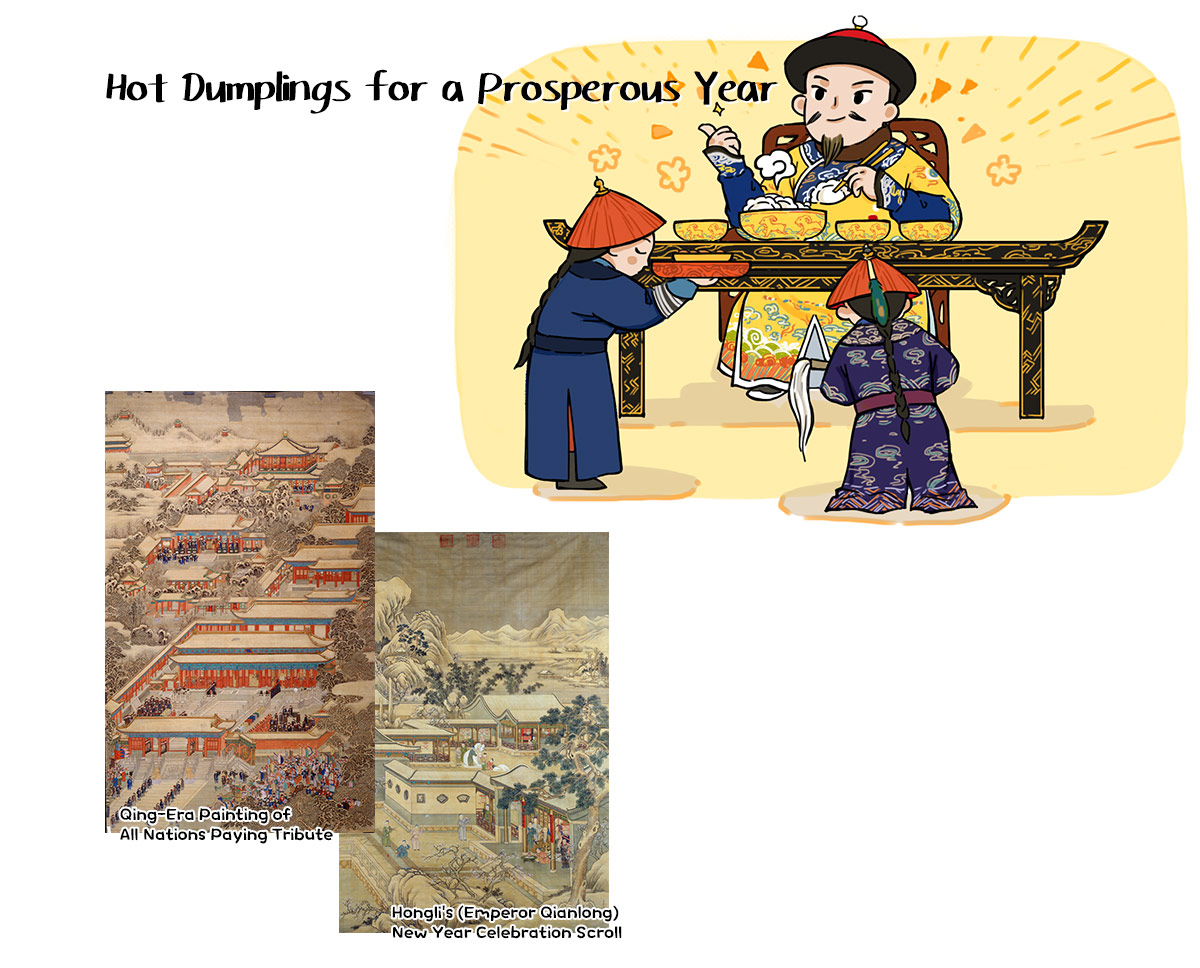

In addition to the family banquet, the emperor would also enjoy a dish of vegetarian dumplings on New Year’s Eve. These dumplings symbolised the “passing of the old year” and reflected the emperor’s remembrance of his ancestors. In Manchu tradition, people began eating dumplings on New Year’s Eve and continued for over ten days, a custom called “eating an over-year meal”, symbolising an annual surplus. Sometimes, a coin-filled dumpling would be added to the pot, and whoever found it was considered the luckiest of the year.

The emperor ate these dumplings alone in a private ritual. For instance, records show Emperor Jiaqing (r. 1796–1820) enjoying dumplings in the Hall of Manifesting Benevolence (Zhaoren dian) of the Palace of Heavenly Purity. On the polished black lacquer table adorned with golden gourd motifs and blessing words “all auspicious”, three enamelled bowls with the motif of “Three Rams Heralding an Auspicious Beginning” held southern pickles, cold dishes, and sauce and vinegar, each with a slip of auspicious words beneath.

The eunuch brought in a red lacquered box decorated with flying dragons, containing two bowls with the motif of “Three Rams Heralding an Auspicious Beginning”, one with vegetarian dumplings and the other with coins from the Qianlong and Jiaqing reigns. The lead eunuch would place the dumpling bowl on the word “auspicious” of the table’s “all auspicious” symbol, kneel, and invite the emperor to enjoy the dumplings. Afterwards, a small dumpling with a slice of red ginger would be placed in a porcelain dish and taken to the Buddhist shrine, while the coins would be delivered to the Hall of Promoting Virtue (Hongde dian) on the east side of the Palace of Heavenly Purity.

As the year turns, prosperity flows. After the emperor completed the First Writing ceremony, he would return to the Hall of Manifesting Benevolence to eat the first dumpling of the New Year. How did the imperial chefs ensure that piping hot dumplings were served the moment the emperor arrived at the hall?