Springtime brings gentle breezes and radiant sunshine, the perfect season for outings to enjoy the beauty of nature. This year, however, due to the pandemic, we must pause our outdoor adventures. Instead, why not immerse ourselves in the warmth of spring through paintings and embark on a “virtual spring outing” across time and space?

Spring outings are a long-cherished tradition. The Tang dynasty (618-907) poet Bai Juyi (772-846) once wrote, “To miss the joys of spring outings is sheer folly.” This verse reflects the ancients’ love for such excursions. Beyond poetry, countless paintings capture scenes of springtime revelry. Among these, Spring Outing by Zhan Ziqian of the Sui dynasty (581-618), housed in the Palace Museum, vividly portrays a springtime journey over a thousand years ago.

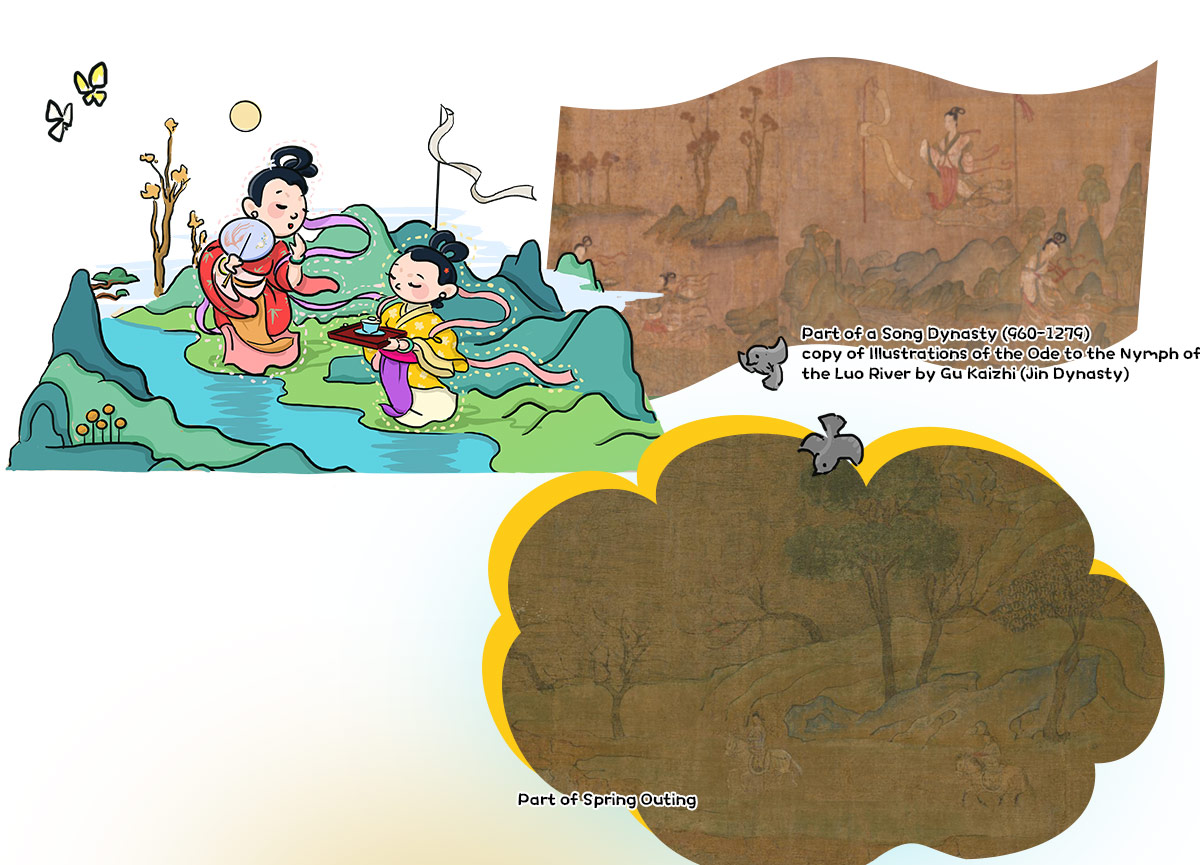

The painting depicts people venturing to riversides and mountains on a bright and breezy spring day. As the scroll unfurls, it reveals a world filled with warm sunlight and vibrant vitality.

Nestled within lush hills and lucid waters veiled in mist, a temple with red walls peeks out discreetly. A gentle stream flows below, where a man on a white horse is to cross a red-arched bridge, accompanied by two companions, all savoring the beauty of the springtime scenery. Ahead lies a vast, shimmering lake, its surface rippling in the breeze. A boat glides gracefully on the water, carrying several ladies engaged in animated conversation, who seem to be enchanted by the surrounding splendor.

With spring in full bloom, let us delve into this painting and uncover the story behind it!

Spring Outing is no ordinary artwork. As a saying goes, “Silk survives 800 years; paper endures a thousand.” This adage refers to the typical lifespan of artwork on silk (which can be preserved for around 800 years) or paper (which can last approximately 1,000 years). Remarkably, Spring Outing, a silk painting, has defied this expectation, enduring for over 1,400 years so far. Though debates over its precise era and authorship persist, it remains an invaluable resource for understanding the early development of landscape painting in China.

The painting is attributed to Zhan Ziqian (c. 545-618), a celebrated artist of the Sui dynasty. Spanning the Northern Qi (550-577), Northern Zhou (557-581), and Sui periods, Zhan excelled in painting figures, horses and carriages, and landscapes, leaving a lasting influence. Yet, due to the passage of time, Spring Outing is his only known surviving work today.

In contrast, Spring Outing from the Sui dynasty marks a transformative leap. The people, buildings, and horses are depicted more proportionately, establishing landscapes as a primary focus, with figures playing only a supporting role in interspersing the complete landscape. This evolution reflects heightened observation and nuanced depiction of natural scenery.

The painting’s artistic techniques also exhibit advancements. Mountain contours and tree branches are meticulously outlined and then filled with ochre, gold, and blue-green. While the trees retain a slight plainness, they are far more lifelike than their stiff predecessors, exuding a vibrant, springtime energy.

Over its 1,400-year history, Spring Outing has been cherished by successive dynasties and now resides in the Palace Museum. Yet, the painting once drifted into private hands and its return was accompanied by a tale of twists and turns.

Previously a part of the Qing court collection, Spring Outing was taken by Puyi (1906-1967), the deposed Emperor Xuantong of the Qing dynasty (1616-1911), when he was expelled from the Forbidden City. It was later taken to Changchun. After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Puyi, then the puppet ruler of Manchukuo, fled in haste, leaving the painting to drift into civilian hands in northeastern China.

In 1946, a batch of scattered artworks began surfacing in the marketplace. News spread in Beijing’s antique circles that a dealer had acquired Zhan Ziqian’s Spring Outing and was seeking a buyer. Upon hearing this, Zhang Boju (1898-1982), a renowned collector and a specially appointed member of the calligraphy and painting committee of the Palace Museum, immediately made inquiries. To his dismay, the asking price was a staggering 800 taels of gold! Undeterred, Zhang employed a clever strategy: he persuaded other antique dealers of the painting’s historical and cultural significance, stressing its importance as a national treasure that must not be lost abroad. This stirred their patriotism and concern for its fate. Eventually, a representative, Mr. Ma Baoshan from the Studio of Treasured Calligraphy and Paintings (Mobao zhai), was sent to negotiate, successfully bringing the price down to 220 taels of gold.

After much effort, Zhang Boju finally purchased the painting. Despite the reduced price, Zhang faced financial difficulty as he had recently purchased several Song and Yuan masterpieces. To secure the funds, he was forced to sell the former residence of Li Lianying (1848-1911), which he had previously bought, to Fu Jen Catholic University in Beijing, ultimately preventing Spring Outing from being lost overseas.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Zhang Boju and his wife Pan Su (1915-1992) donated Spring Outing along with dozens of other precious artefacts to the state. Thanks to their generosity, we can now admire this masterpiece in the Palace Museum.