When we wish someone well, we often say, “May everything go as you wish.” But do you know what a ruyi (“as you wish”) actually is? In terms of appearance, it resembles clouds or Ganoderma lucidum (lingzhi), symbolizing auspiciousness and happiness. Yet originally, a ruyi wasn’t a symbolic artefact of blessings but rather something entirely different.

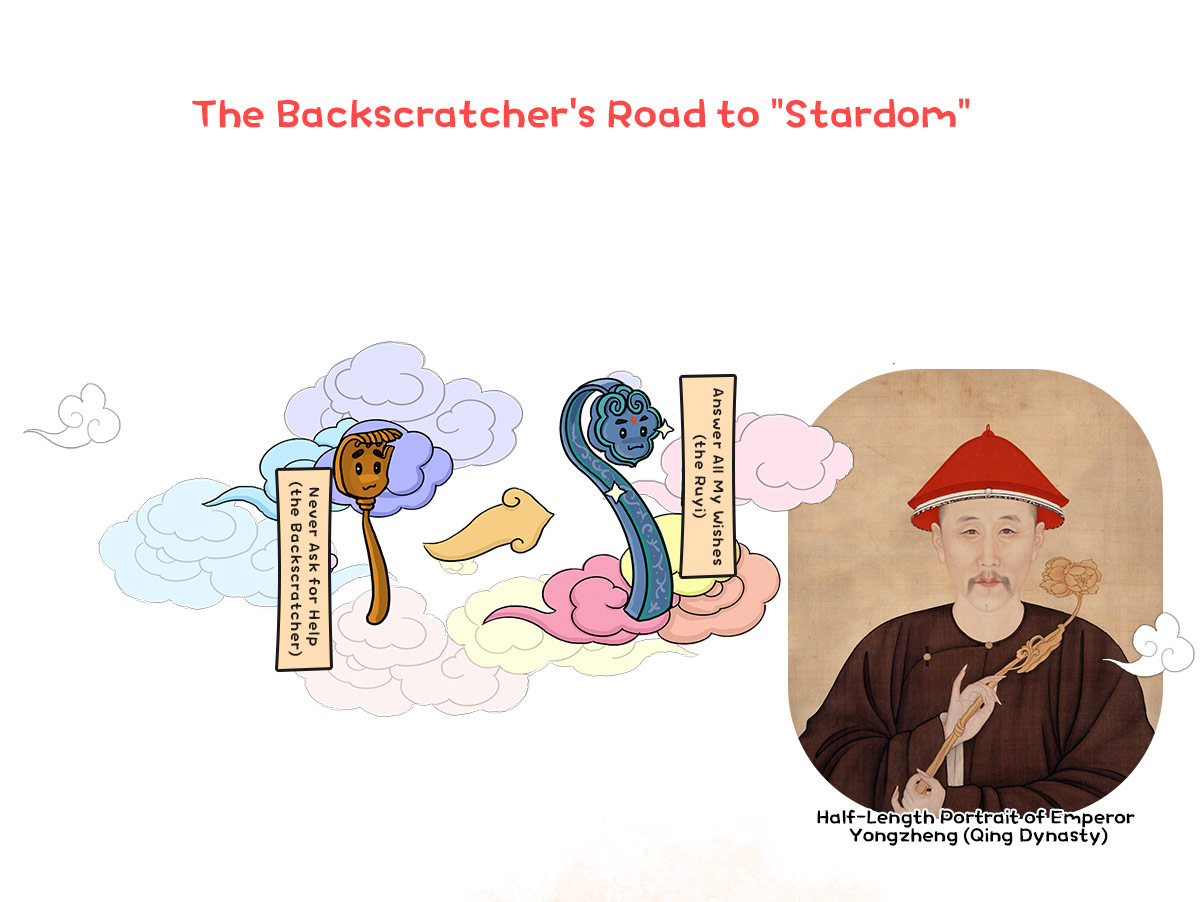

Here’s a question: What can you do when your back itches, but your arms are not that long? Please join me in welcoming the backscratcher! In ancient China, there was a tool similar to today’s backscratcher—zhaozhang (“claw staff”). Since it could scratch where needed, it came to be associated with the idea of “fulfilling one’s wishes,” becoming the precursor of the ruyi. However, the ruyi wasn’t content to be merely a practical tool; it embarked on a journey to “stardom.”

The ruyi had its first moment of glory during the Wei and Jin dynasties (220-420), tied closely to the rise of Buddhism. Alongside tools like ear picks, monks’ staffs, and tongue scrapers, backscratchers became part of the monks’ everyday gear. It’s speculated that the aristocratic elites of the time, who advocated “pure conversation” (discussions and debates about metaphysics and philosophy), borrowed this item originally for Buddhist practices from the monks, and thereby the ruyi entered “high society.”Today, if you visit the Palace Museum, you’ll see ruyi displayed prominently in palace halls—beside thrones, on tables, or near beds—demonstrating the royal court’s fondness for them. The Palace Museum alone houses over 2,000 ruyi pieces, including those tributed by local officials and those crafted by artisans of the Imperial Workshop.

The variety of ruyi is astonishing, crafted from materials such as metal, jade, bamboo, and wood, all with exceptional craftsmanship and diverse designs. For instance, Emperor Qianlong (r. 1735-1796) pioneered a three-inlay ruyi design, allowing ancient jade to be set in the head, middle, and tail of the scepter—combining auspicious symbolism with the tactile pleasure of admiring jade.

Many ruyi pieces are further adorned with auspicious motifs such as lingzhi, fruits, eight immortals, and pavilions. For example, chayote symbolizes abundant blessings, peaches carry wishes for longevity, and lotus flowers paired with swallows represent that peace reigns under heaven (In Chinese, lotus “荷” and river “河” are homophones, as are swallow “燕” and peaceful “晏”). Also, the vines entwining the ruyi signify a prosperous family and a flourishing lineage.

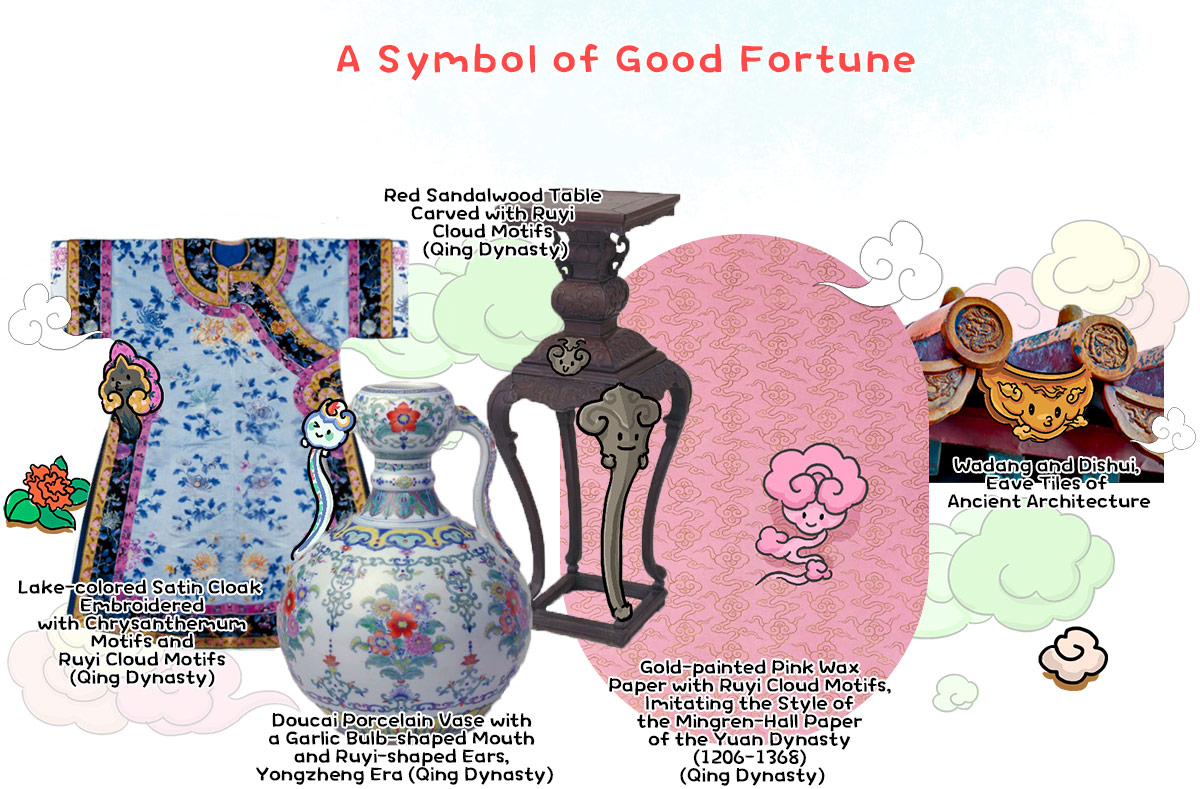

Now look closely at the ruyi. Its head is beautifully shaped, often resembling auspicious clouds—a feature initially inspired by lingzhi or cirrus clouds. By the Ming and Qing periods, the ruyi had become so ingrained in popular consciousness that cloud-like decorative motifs were simply named the ruyi cloud motifs, adorning everything to add a touch of beauty and auspiciousness to royal life.

The ear-like handles of porcelain vessels, gracefully curved, are named ruyi ears for their resemblance to the auspicious ruyi. Ancient furniture is also often graced with ruyi cloud motifs. The large ruyi cloud motifs embedded in the edges of garments create a dynamic and splendid touch. On pink wax paper, the ruyi cloud patterns appear both refined and ravishing, carrying wishes for good fortune. Looking up to the eaves of buildings in the Forbidden City, you’ll see upturning tiles called wadang that function to prevent rainwater from seeping in, and down-turning titles called dishui that guide the flow of rainwater. Wadang is often round, while dishui is crafted in the shape of ruyi clouds. Together, they form a harmonious union, appearing like endless undulating waves when viewed from afar, protecting the ancient buildings in the Forbidden City from rain erosion. Take a closer look, and you’ll find more ruyi motifs hidden within the Forbidden City.

The ruyi carved with bamboo or wood gained popularity in the late Ming and early Qing periods due to their lightness, perfect for toying with. Their understated elegance particularly won the favor of Emperor Qianlong.

The ennead of ruyi was often used at festive celebrations in the royal palace or as a gift for imperial birthdays. In ancient China, “nine” symbolized the pinnacle of numbers, so this ennead carried wishes for boundless longevity.

These include ruyi scepters made from gold, silver, copper, iron, and various alloys, with the most intricate being gold and silver filigree designs.

From the mid-Qing dynasty, the jade ruyi became particularly popular among the upper classes due to the ample supply of jade. They come in many varieties, including white jade, green jade, jasper, black jade, emerald, crystal, malachite, and agate.