During the 16th and 17th centuries, Galileo (1564-1642) began using telescopes to observe the moon, Copernicus (1473-1543) proposed the heliocentric theory, and Columbus (1451-1506) discovered the Americas through his sea voyages. In an age when travel relied on carriages and sailboats, such scientific theories and relevant instruments also made their way into the Qing royal court: Galileo telescopes, orreries demonstrating the heliocentric model, horizontal sundials, and astronomical observation devices. Who brought these innovations into the Forbidden City? Let us take a look together.

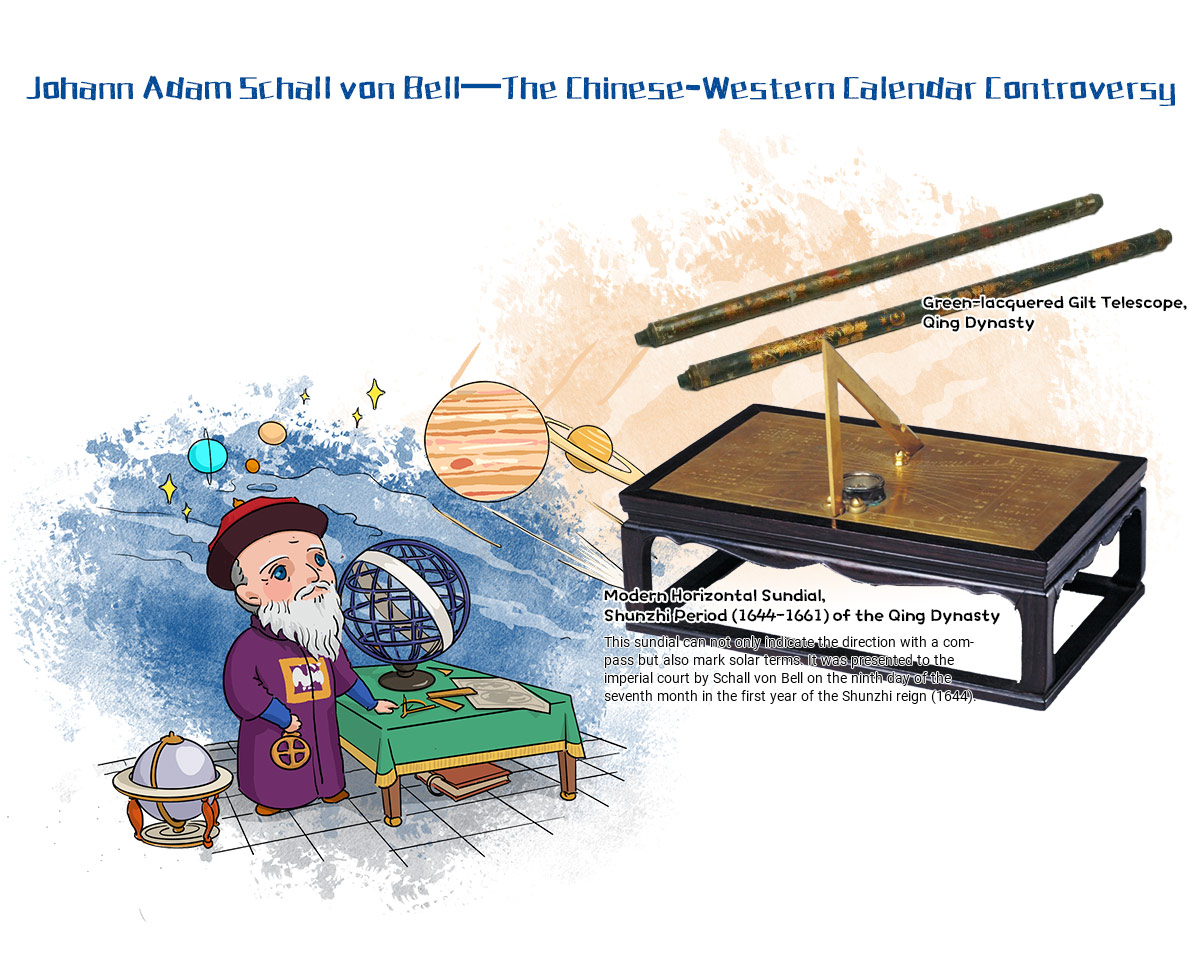

From the Wanli period (1572-1620) of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) from Italy and Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591-1666) from Germany, among other Western missionaries, arrived in Beijing. While spreading their religious teachings, they also served the royal court, bringing novel items such as dispersive prisms, striking clocks, and Western musical instruments. Schall von Bell’s Treatise on Telescopes introduced Galileo telescopes to the Chinese royal court.

By the Shunzhi period of the Qing dynasty, Schall von Bell and others were still working in the Imperial Astronomical Bureau (which was responsible for observing celestial phenomena and creating calendars). Over time, however, the Datong calendar and the Hijri calendar adopted by the bureau had become outdated. Schall von Bell introduced Western scientific instruments for astronomical observations and calculations, producing devices such as the modern horizontal sundial and recompiled a new calendar, the Shixian calendar.

The new calendar’s publication sparked dissatisfaction among conservative officials. After the death of Emperor Shunzhi (r. 1644-1661), when the eight-year-old Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661-1722) ascended the throne, the Qing government was held by four regents led by Oboi (1610-1669), who supported conservative factions represented by Yang Guangxian (1597-1669). Slandering the new calendar as an “absurdity,” they attacked Schall von Bell and other missionaries, imprisoning them alongside several officials from the Imperial Astronomical Bureau. Yang Guangxian was subsequently appointed as the director of the bureau.

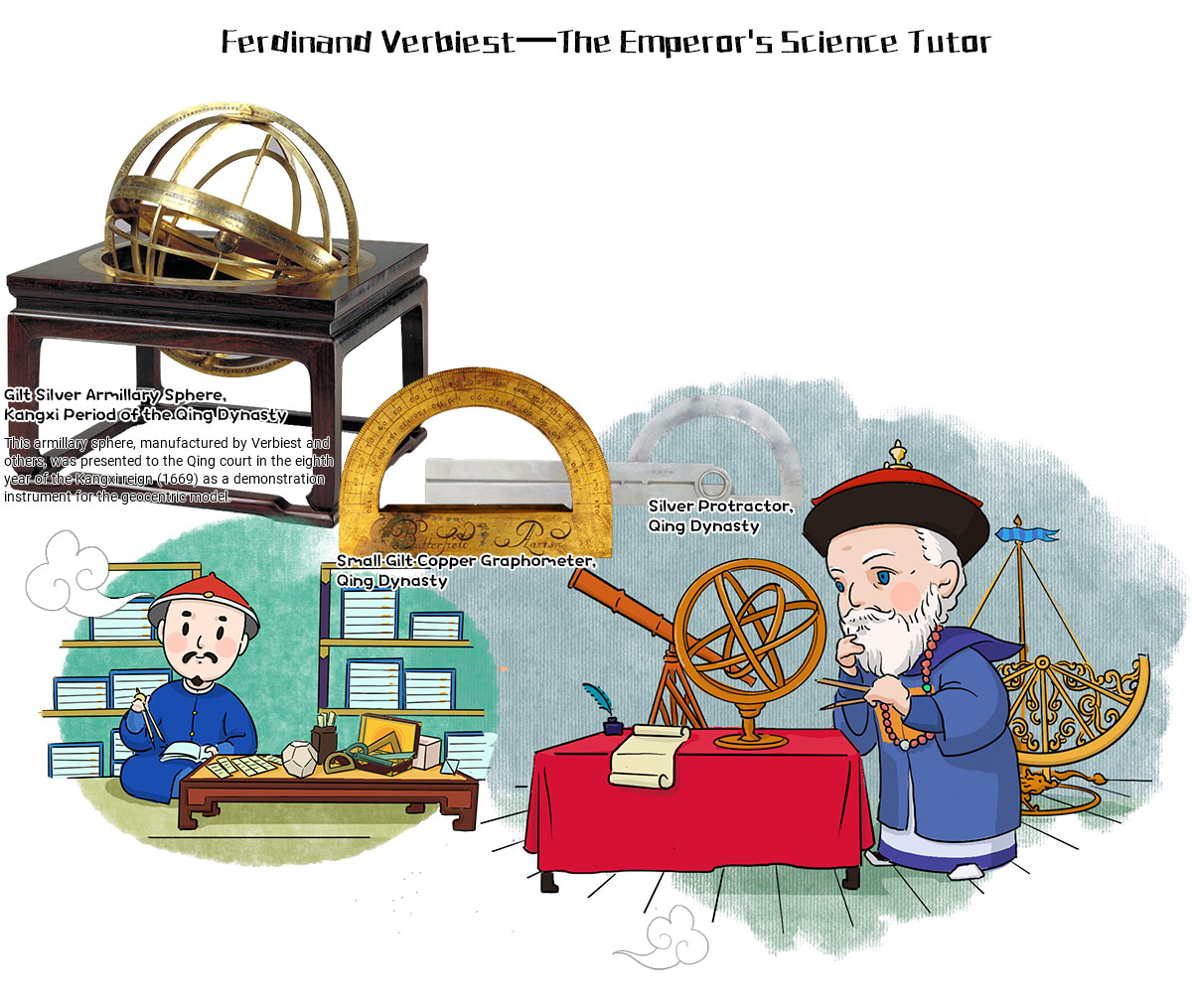

Following the calendar dispute, Verbiest was summoned to the court by the young Emperor Kangxi to serve with his expertise in mechanics, astronomy, geography, and other Western sciences. During his tenure as director of the Imperial Astronomical Bureau, Verbiest redesigned the Imperial Observatory in Beijing, and equipped it with six newly cast large astronomical instruments. As the emperor’s tutor, he taught Emperor Kangxi geometry and astronomy, translated Euclid’s Elements into Manchu, and accompanied the emperor on tours while conducting astronomical observations and geographic surveys along the way.

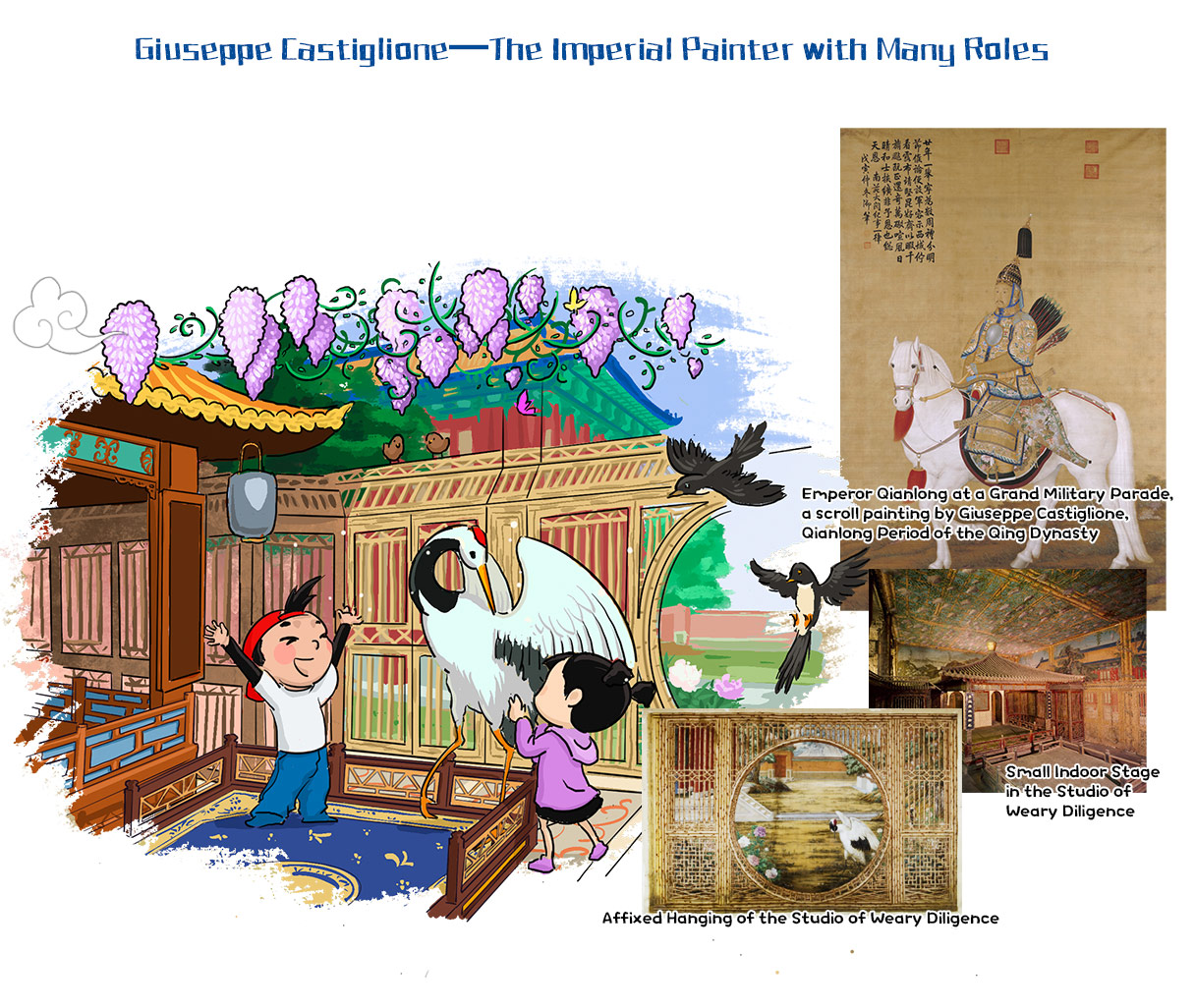

By the Qianlong period (1736-1795), the emperor’s fascination with mathematics and science had waned, but Italian missionary Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) and others continued serving as a royal painter in the Hall for Fulfilling Wishes and Aspirations (Ruyi guan). They brought Western painting techniques, particularly realism, to the imperial court, capturing many significant historical moments for the emperor. Castiglione also had expertise in Western architecture. Alongside French missionaries Michel Benoist (1715-1774) and Jean-Denis Attiret (1702-1768), he participated in the design and decoration of imperial buildings and gardens, such as those in the Forbidden City and the Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace). The European technique of perspective was applied to the affixed hangings (tieluo) of walls and ceilings, creating an illusionary blend with real interiors, known as scenic illusion painting, or tongjing painting. These paintings, which seamlessly combined illusion and reality, were adored by the royal court.

In the Studio of Weary Diligence (Juanqin zhai) of the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (Ningshou gong), you can still find an exquisite scenic illusion painting believed to have been painted by Castiglione’s students, modelled after his works in the Palace of Established Happiness (Jianfu gong) and the Palace of Universal Happiness (Xianfu gong). Within a compact space, the affixed hanging’s depiction of rocks, trees, pavilions, and corridors seamlessly blends with the small indoor stage, creating the illusion of walking through a circular “moon gate” into a garden to frolic with cranes and magpies after enjoying the play. Now look up: the ceiling resembles a pergola of bamboo and wisteria vines, with clusters of pink-purple blossoms cascading downward. Standing in the center of the room, you will perceive a cluster of flowers suspended directly above, with the surrounding ones artfully tilted, creating a dynamic visual effect. No matter where you stand, the blossoms appear to sway, making you feel as though you are truly beneath a flowering arbor.

Western scientists brought Europe’s advanced sciences and arts to China, while also introducing Chinese culture and customs to Europe. Through their letters and writings, they provided people in distant Europe with a glimpse into China’s splendor.