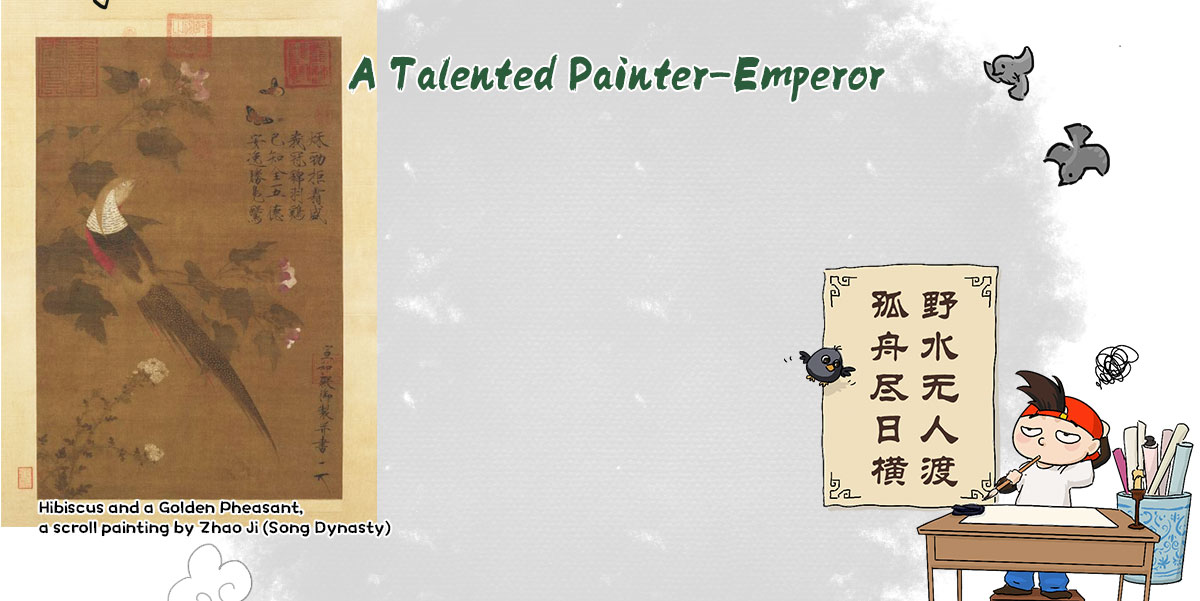

Among the many flower-and-bird paintings of the Song dynasty (960-1279), Loquats and a Mountain Bird stands out as a famous masterpiece. In this painting, two branches laden with loquats are rendered in ink, and a small bird perches delicately on a branch, its gaze fixed intently on a fluttering butterfly through the foliage. The artwork is incredibly realistic, vividly depicting details such as the small holes eaten through the leaves by insects and the plump, juicy loquats. The painter was none other than Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) —Zhao Ji (r. 1082-1135).

On the other half of this folio, Emperor Qianlong (r. 1735-1796) of the Qing dynasty (1616-1911) composed a poem dedicated to this painting: “So round, so full, and oviform, Loquat thus earns its name. Its form shows the silent grace, Why bother seeking its own voice? The bird perches steadfast on the tree, While the flitting butterfly is so free. Emperor Huizong’s artistry is finest, Why did he have the capital lost?” Emperor Qianlong lamented that Emperor Huizong failed to keep his capital and brought ruin to the Northern Song dynasty. While he was an unfit ruler, his extraordinary talent in art made him a top-tier artist—a historical irony indeed.

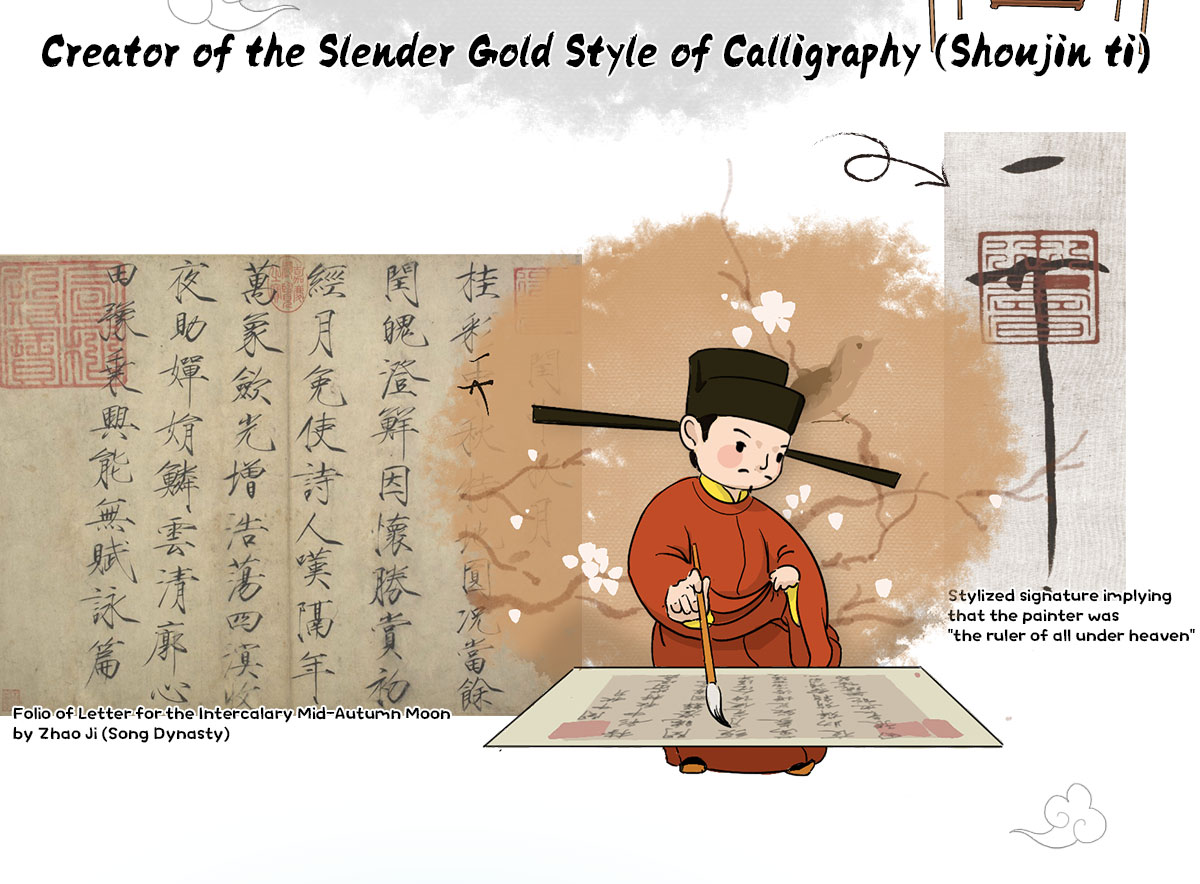

Emperor Huizong devoted his life to the pursuit of art. The rough estimate reveals that, aside from Loquats and a Mountain Bird, over 20 of his paintings remain extant today, making him the Northern Song artist with the most surviving works. The Palace Museum holds several of his renowned pieces, such as Listening to the Guqin, Hibiscus and a Golden Pheasant, and Plum Blossoms and a Warbling White-Eye. Though some speculate that he occasionally employed other court painters to assist him, his advocacy for blending poetry and painting gave Song court art an elegant and poetic charm.

On one occasion, Emperor Huizong ordered painters to create works based on the following verse: “Far and wide waters flowing, no one rows, Days and nights turning, one boat lies.” Most painters depicted an empty boat moored to the shore to emphasize “no one.” However, the artist Song Zifang (1101-1125) interpreted it differently—he painted a boatman reclining at the stern and playing a flute. Instead of highlighting the absence of people in the boat, his rendition emphasized the vast emptiness of the surroundings, with no passers-by, and the boatman’s leisurely serenity. This ingenious artistic interpretation of the verse won Emperor Huizong’s applaud.

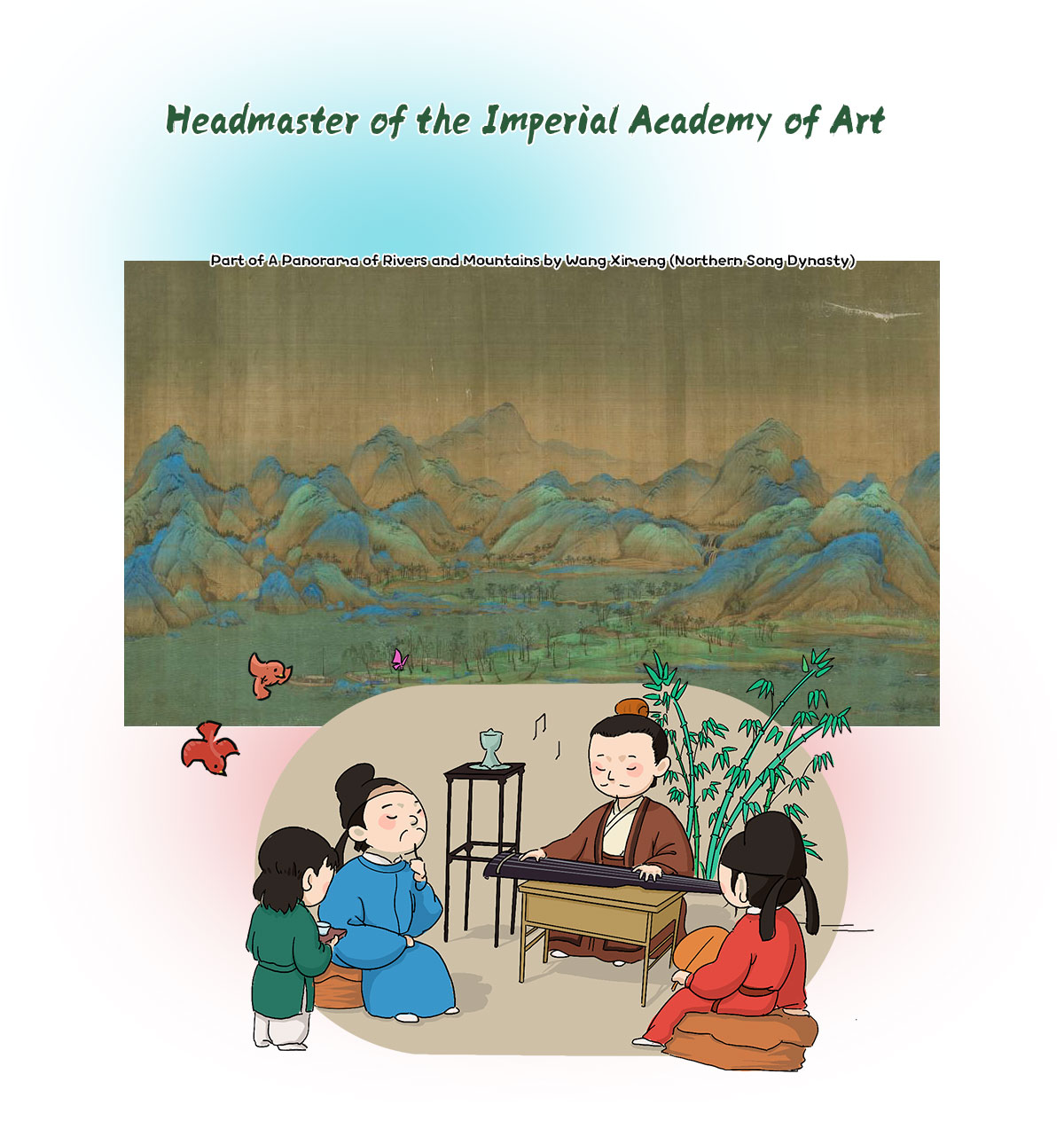

Emperor Huizong not only excelled in art himself but also prioritized the cultivation of artistic talent. He established the Song dynasty’s highest government-run art academy—the Painting Academy. Unlike the imperial Hanlin Painting Academy, this was a dedicated educational institution for painting and the only royal painting school in Chinese history. For the people of that time, studying for the imperial examination was no longer the only path to officialdom; those with painting skills could also achieve success, elevating the status of painters to unprecedented heights.

The Painting Academy boasted a formidable faculty, including renowned calligrapher and painter Mi Fu (1051-1107). Emperor Huizong himself often visited to provide guidance. Wang Ximeng (1096-1119), the creator of the national treasure A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains, was a student of this academy. After graduation, Wang Ximeng presented his works to Emperor Huizong on several occasions. While Emperor Huizong initially criticized his lack of skill, he recognized Wang Ximeng’s artistic potential and personally mentored him—a unique “teacher-student” bond. It is said that A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains was painted under Emperor Huizong’s guidance, with the silk canvas and pigments specially supplied by the emperor himself.

Emperor Huizong was also an enthusiastic art collector. He compiled the imperial collection of artworks into a book titled the Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings. More than a simple catalogue, this book serves as a biographical history of Chinese painting. It includes 6,396 works divided into ten categories, such as figure paintings, landscape paintings, and flower-and-bird paintings. Each category is prefaced by an essay that details its origins, development, and representative artists, followed by chronological introductions of painters and their works. The catalogue has provided invaluable materials for the study of the painting history of the Northern Song dynasty and before. In addition to the Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings, Emperor Huizong organized the compilation of the Xuanhe Catalogue of Calligraphy, which catalogues the imperial collection of calligraphic masterpieces. This work, also thorough and detailed, has preserved numerous important historical records that might have otherwise been lost to time.