Dolphins leap out of the sea, rays have long tails, whales spout water when breathing, and cuttlefish squirt ink to confuse predators. We can learn these fascinating facts from books, cartoons, or the aquarium. But have you ever wondered how ancient people, including emperors who rarely ventured beyond the palace walls, came to know about these marine creatures?

Believe it or not, the people in Qing dynasty (1616-1911) may also be familiar with these! Why is it possible? The answer lies in a remarkable collection of illustrations known as the Haicuotu (Illustrations of Sea Creatures), which served as an ancient “marine life encyclopedia.” Here’s what makes this set of drawings so extraordinary.

Originally, Haicuotu was completed over 300 years ago during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661-1722) of the Qing dynasty. It comprises four volumes. At that time, navigation technology was far inferior to today, yet Haicuotu managed to document 371 species of marine-related organisms, earning it the title of an oceanarium on paper during its time.

So, what does the name Haicuotu(海错图, lit. the errors of the sea)mean? Of course, it doesn’t imply an abundance of errors. Here, the character “错” refers to a great variety and diversity. Prior to the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), people used the term“海错”to refer to various marine organisms.

As you flip through the illustrated collection, you will encounter a vast array of stunning sea creatures such as the fearsome tiger shark and the endearing mackerel, alongside marine plants like seaweed and laver. You will also be attracted by mythical beings passed down through oral traditions, such as the fierce cannibalistic sea spider, or the “sea monk” with a turtle body and a human head. In a word, you will definitely be dazzled by the sheer diversity of Haicuotu!

In addition to the illustrations, each creature is accompanied by a descriptive text. These texts delve into the origins, habits, physical characteristics of the organism, exploring its culinary uses and medicinal value, providing valuable reference materials for modern-day research into marine animals and their history.

So, who exactly was the creator of Haicuotu?

His name was Nie Huang, a painter of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, and also an avid enthusiast of biology. Nie noticed that painters preferred to depict subjects like plum blossoms, orchids, bamboos, chrysanthemums, birds, beasts, and human figures, yet few painted marine life in a systematic way. This inspired him to take on this challenge himself.

During the Kangxi reign, Nie traveled to Hebei, Tianjin, Zhejiang, Fujian and other places, observing coastal creatures along the way. Whenever he encountered a new marine species, he would sketch it, and write explanatory notes for it by referring to relevant documents or consulting local fishermen.

Gradually, he drew more and more marine life in his collection. In the summer of 1698, Haicuotu was finally completed. However, from that moment on, Nie Huang mysteriously vanished from historical records, and the whereabouts of his works also became a mystery. It was not until the year of 1726 that Haicuotu resurfaced. According to palace records from that year, a eunuch named Su Peisheng had brought it into the imperial palace.

You must be aware that the emperors of the Qing dynasty were from the Manchu ethnicity in the north, who have rare opportunities to come closer to the sea or witness the bizarre marine creatures. Furthermore, there were very few books on marine life in ancient China. No wonder emperors such as Qianlong (r. 1736-1795), Jiaqing(r. 1796-1820), and Xuantong(r. 1909-1912) were fascinated by Haicuotu. Emperor Qianlong even ordered eunuchs more than once to rebind Haicuotu and had it placed in the palaces he frequently visited for easy access.

During the Republic of China era (1912-1949), the artifacts of the Forbidden City were relocated southward due to Japan’s invasion of China. In the process, the four volumes of Haicuotu became separated. Currently, the first three volumes are housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing, while the fourth volume is kept in the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

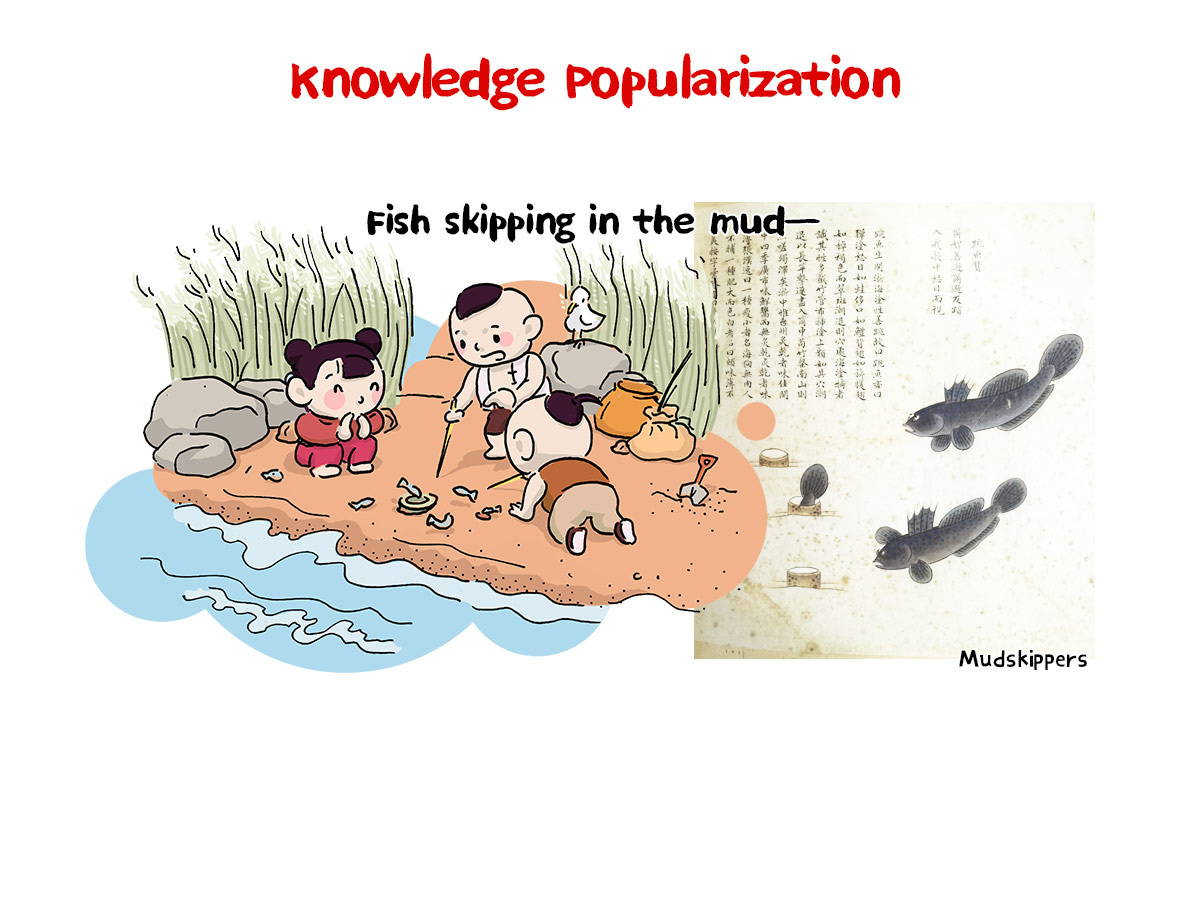

How many little fish are there in the above picture? Two or three?

Yes, keen-eyed audience must have noticed that there is a little fish partly buried in the sand, hiding like it’s playing hide-and-seek and leaving only a small tail exposed.

This fish is a common species found along the coast—the mudskipper. It’s known as the “skipping fish” in Haicuotu because of its ability to skip on mud flats. Mudskippers love to crawl out of the water and move around on beaches. At low tide, many of them can be seen jumping around on the beach. Additionally, they enjoy digging holes in the mud flats and retreat into the holes when in danger.

Through Haicuotu, people not only learned about mudskippers but grasped the methods of capturing them. According to Haicuotu, fishermen would insert bamboo tubes into the holes dug by mudskippers and then use long poles to drive them out. At last, the mudskippers unconsciously fall into the bamboo trap. It is said that even today, fishermen in Ningbo, Zhejiang, still use this method to catch mudskippers.

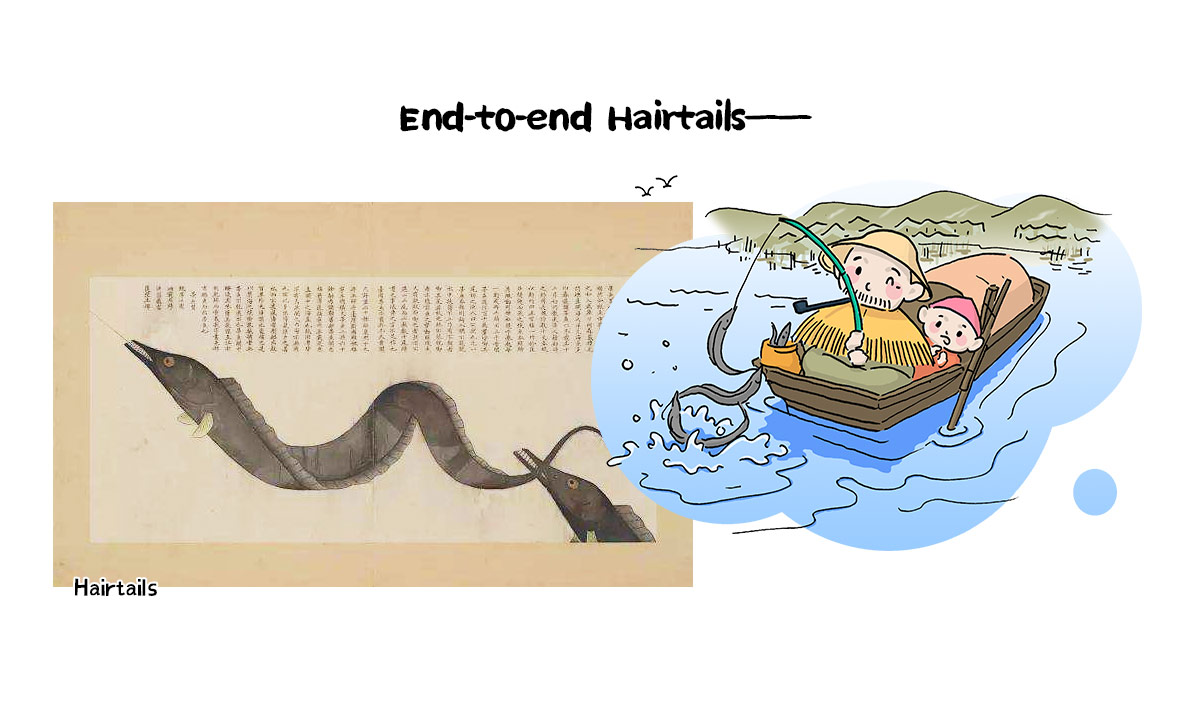

Upon your first sight of this drawing, you might wonder why the hairtail at the bottom right corner is biting the tail of the one in front.

Fishermen shared with Nie Huang the reason for this. They said that hairtails often swim in groups in the water. When one of them is caught on the hook and struggles in the water, other hairtails will instinctively bite onto its tail, trying to rescue it, only to find themselves pulled up as well. Therefore, fishermen can sometimes catch two or three hairtails strung together in one go!

Today, we can still observe this fascinating phenomenon by the seaside. However, when it comes to the records of hairtails in Haicuotu, it only tells half the story. The other hairtails actually are not trying to rescue the hooked one; rather, the struggle of the hooked fish triggers their appetite, and other hairtails just want to nibble at it, only to accidentally end up losing their own lives.

Intriguingly, Haicuotu also introduces the common way of cooking hairtails in the Qing dynasty—pickled hairtails. Nie Huan even went on to comment that the salted hairtails from Fujian were just average in taste, whereas those from Zhejiang were truly delicious.

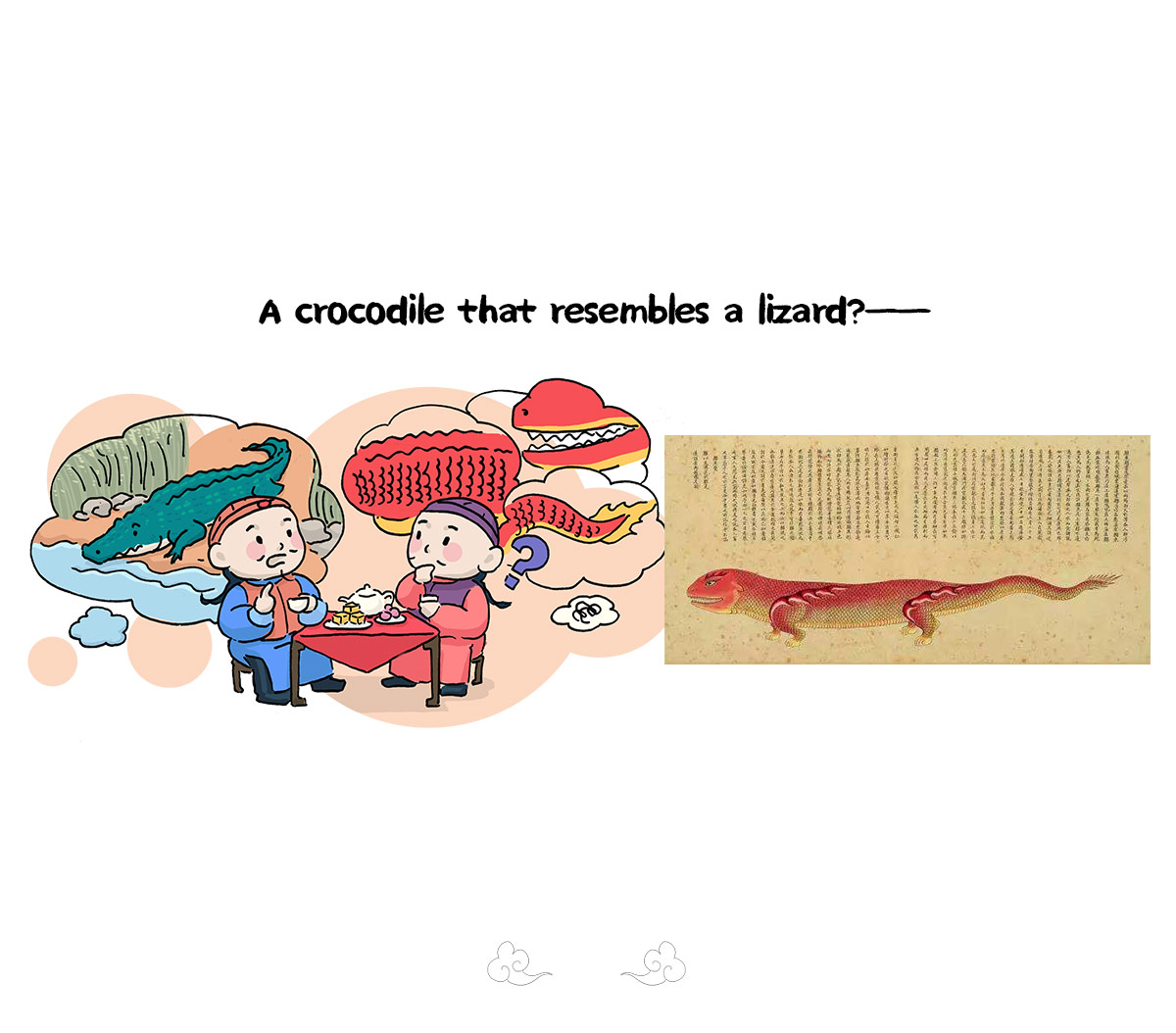

Some of the marine creatures recorded in the Haicuotu were based on hearsay. For instance, is this a lizard in the picture above? No, it’s a crocodile!

Why does it look so different from the crocodiles we know? Because Nie Huang recorded many creatures that he had only heard of when he compiled the Haicuotu. For example, the crocodile in the illustration was something Nie had never seen before. He wrote in the Haicuotu that a Fujianese named Yu Bojin told him about crocodiles. Yu encountered two crocodiles in Annam (present-day Vietnam) and gave Nie a detailed account of their appearance: “Measuring over 6 meters in length, they had armored bodies, short limbs with claws, square and wide mouths, and flat tails that were not pointed.” After all, hearsay is not always reliable. The crocodile drawn by Nie still differs from a real crocodile, which produces a sense of humor and amusement.

In the Qing dynasty, the Haicuotu served as a window through which people gained insight into the mysterious world of the ocean, ventured into territories they had never been to before, broadened their horizons, and enriched their knowledge. Have you noticed? The Haicuotu is not merely a book of marine life; it is also a fishing guidebook and a recipe book for seafood cuisine! If you find this collection interesting, you can search for this book, or purchase it if you want, and embark on a joyful journey through the wonders of the ocean!